The partnership combines ESPROS’ NIR silicon imagers with Viavi’s filter technology.

The spectral sensor combines Viavi’s 64-channel micro-patterned bandpass filter array and the ESPROS hybrid CCD-CMOS imager, to make a spectral sensor that is 2.7 x 2.7 x 1.1mm.

Two versions will be offered – one for the visible range (385-900nm) and one for the NIR (775-1065nm).

Potential for use in smartphones

The firms said the size and projected cost of the sensor should bring sophisticated wavelength analysis and shortwave near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy within reach of devices such as smartphones.

The sensor could help consumers analyze the composition of food, beverages and medications.

Chris Pederson, product line manager of MicroNIR at Viavi Solutions, said over the last decade the food and beverage industry has had wide access to NIR spectral systems for applications such as quality control, monitoring and measuring fat and protein.

“The high end spectral systems are at a price point in excess of $50,000 and need a scientist to operate. What has happened for several years now is that companies push to deploy simpler, handheld, portable, out of lab versions and take the spectrometer out in the field to get a quality assessment and then you know how to handle and process the sample appropriately,” he said.

“It is in its infancy at this point but smartphones are capable of the computing power, the sensor can give results customers are demanding.”

A sensor could give information on the nutritional composition of materials – protein, fat, sugar and the freshness test of fruit, meat and beverages. NIR is also used for fraudulent products such as fine spirits diluted with water.

Pederson said the performance of any application of NIR spectroscopy is only as good as the calibration database behind the sensor.

“With protein analysis you need to train the spectroscopy technology. Commercial food and beverage companies have done this for years and they have the information, which operates in the background, in detailed, vast calibration libraries. Calibration libraries are needed to make spectroscopy work effectively,” he said.

“With the food and beverage manufacturer they know the spectrum of the product they manufacture but it is random with the consumer.

“[The time it takes] to build the method behind the spectral sensor is application dependent. With food on a plate in a random restaurant, the method has to encounter the variations you would expect to see. Predicted results are only as good as the library behind it.

“In the traditional instrumentation space there are a lot of standards such as NIST, AOAC methods and standard methods used by food and beverage companies for several decades in building up their spectral capabilities. If people spend the time, and do the science, that will determine the validity of the sensors.”

Developer kit and application potential

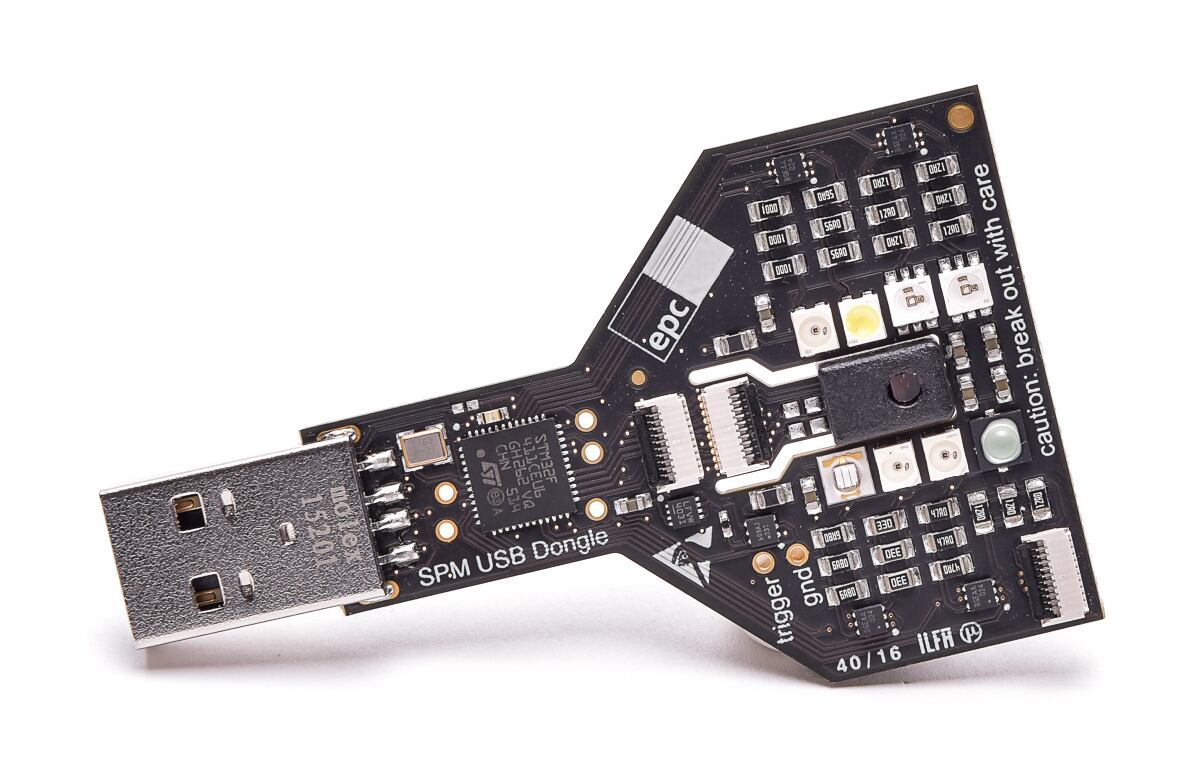

Viavi and ESPROS unveiled the SPM64 Developer Kit to build the market and enable customers to develop applications.

It includes a prototype sensor mounted on a USB dongle-style circuit board with a microcontroller and various light sources.

The board, when connected via USB to a computer running supplied software, sends pre-processed spectral information to the graphical user interface and optionally a data file.

A supplied application programming interface allows customers to write their own software to control the light sources and sensor, and to acquire and analyze data.

Steve Saxe, product line manager at Viavi Solutions, said ESPROS was looking for a partner to build specific filters and Viavi had developed Binary Multispectral Sensor (BMS) filters.

“The chip is launching in three or four quarters, with the developer kit we will get feedback on what the chip will look like, it is a prototype,” he said.

“In the visible deep blue we expect it to be used more in applications such as printing and photography. The NIR has the tail-end of the visible to give an insight of the chemical composition of material.”

Saxe said the customer decides what to do with the chip as they develop the application.

“Reliability or integrity of measurements depends, as when in the lab you have controlled conditions in terms of what light is in the sample. There is a risk people take information to mean what they think it means and that is not what it really means and maybe that will reach the level of regulation.

“We are hoping to accomplish a sensor technology that is down in size and cost and can be deployed. With the sensor based on silicon-tech we are going to see widespread deployment but that will take two or more years.”