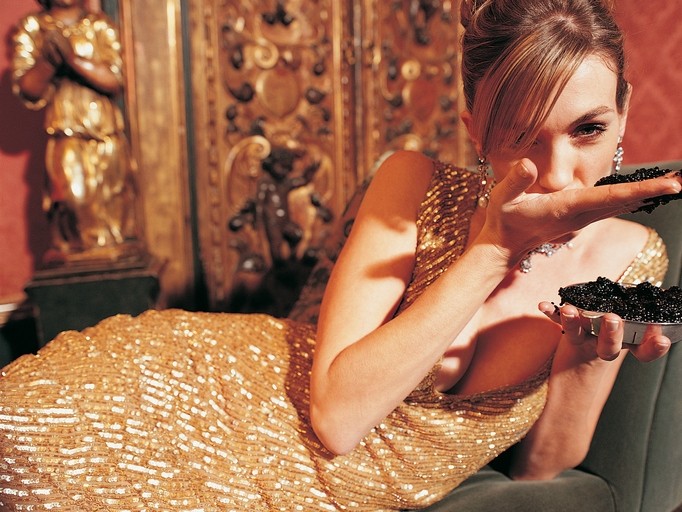

Cell-based caviar: the mass-market health food star of the future?

Caviar is renowned as an exclusive luxury typically only enjoyed by champagne-swilling elites in five-star suites or on-board first-class flights or cruises. But it's also one of the easiest foods to grow in a lab. So says Kenneth Benning, the refined CEO of Exmoor Caviar – famous as the UK's first sturgeon caviar farm. It has been operating in the picturesque English countryside in Devon since 2012 and now supplies its products into leading hotels and over 80 Michelin-starred restaurants.

Benning, however, believes it will become increasingly socially unacceptable in coming decades to eat caviar, which is made from the unfertilised eggs, called oocytes, of sturgeon fish.

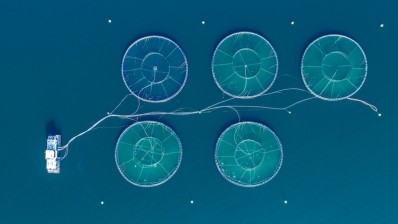

The sturgeon at Exmoor Caviar enjoy a semi-wild, non-caged life. But the entrepreneur told FoodNavigator he believes comprised standards of animal farming husbandry at intensive farming operations in other parts of the world will discredit the caviar name. Consumer preferences, he says, including among traditional caviar buyers, are accelerating towards animal-free foods boasting better sustainability credentials, reduced carbon footprint, and free from antibiotics and chemicals.

Studies support this belief. High society wants its fine foods to also be ethical, according to a 2019 study from the University of British Colombia. It claimed that while upper classes once looked to opera or French cuisine, elites are now signalling their status through ethical foods. A new ‘green’ cachet is taking hold, said the study, with people paying more for products with environmental benefits.

"If you're saying, 'Oh, I should go to this new hipster food truck or this new restaurant that opened up,' that's not even enough anymore to signal that you're high-status," said UBC sociology professor and the study’s lead author, Emily Huddart Kennedy. "Now, it also has to have this additional layer of being good for people and good for the planet."

Ethical food, it seems, is the new ostentatiousness.

Let them eat caviar

In response to the future trends he forecasts, Benning’s other company, called Caviar Biotec, has created a R&D programme to pioneer the ability to grow caviar outside of the sturgeon fish. Caviar Biotec already supplies caviar oil to the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries. This oil is found in the roe sacks that protect the eggs used for the caviar and contains a high concentration of omega-3 and other prized nutrients.

The company is now developing three 'fusion' or ‘clean’ caviar products that are made without harming the fish. The first, or ‘fusion caviar one’, takes the proteins and lipids from sturgeon roe sacks which are then grown using spherification technology into a caviar product -- effectively a fake caviar made from real caviar. This product is likely to appear on supermarket shelves in coming months. The second product, or 'fusion caviar two', involves growing the same proteins and lipids from the sturgeon roe in a bioreactor to make a cell- and animal-free protein powder. Next is ‘fusion caviar three’ or a ‘cell-grown’ caviar. This is made from sturgeon cells put in a bioreactor with hormones, such as proteins and certain molecules, to help the cells multiply and grow.

Caviar Biotec has yet to submit a Novel Foods application in Europe for its two lab-grown products, but it expects to be able to demonstrate products within six months and to get to market within two years.

Cheaper than the real thing

Real caviar can take between seven and 35 years to make depending on the species. Benning expects his lab-grown caviar to be significantly less expensive than traditional caviar as he hopes to produce large amounts in a shorter time.

“It will cost more than any of the faux caviars using lumpfish, trout or salmon etc and it will cost less than the entry caviars that are produced by the Chinese in bulk,” he said.

“If we get to the stage where we can grow 500 kilos of caviar within between 10 and 99 days, given that the caviar industry takes seven years to 35 to be produced then we should be able to produce more caviar per year in less than 100 days in a 300 sq metre room than the entire caviar industry put together.”

Bringing a luxury product to the masses

Benning said the products will have the same taste and texture profile as the real thing and are a “natural progression” in response to growing interest from consumers looking for healthier, more environmentally friendly, sustainable and ethical alternatives to animal proteins. “There’s a younger generation coming through that will decide the food market in 20 years’ time,” he said. “Plant-based food and cell-ag will be viewed very differently.”

Meanwhile, there’s a growing market for caviar among the rising middle-class numbers in China, India and Russia. According to Benning, only about 500 tonnes of caviar is currently produced globally each year, compared to about 3,000 tonnes back in the 1980s. Meanwhile, around 80,000 tonnes of alternative or faux caviar – typically made with herring, lumpfish or salmon roe – is produced each year. “A market for cell-based caviar is perfectly feasible if you bring the price down and raise the quality and production,” he told us.

Benning is therefore initially looking to target the traditional high-end caviar-buying sector such as airlines, cruise liners and people in first class who get it as part of the service, before coming down into the broader market.

“Our existing end-customers are of a certain age and have a certain income. Further down the line, this product is going to be much more cost-effective because of the way we'll produce it, and more importantly, it ticks boxes that at the moment caviar cannot tick.”

Better than the real thing?

For example, cell-based technology offers the chance to produce caviar beads of a specified size, the bigger being the more desirable. Benning said he’ll also be able to recreate different caviar types: beluga, for example, has a richer, creamier taste than sevruga or osetra sturgeon. Cell-based technology also offers the tantalising opportunity to reproduce caviars from critically endangered species and recreate eating experiences that are no longer possible. A ban on the global trade of wild caviar has been in place since the 2000s, for example. But Benning noted there is a substantial difference between the fatty acid profile of wild caviar versus farmed caviar. Now, though, Benning can “manipulate that environment and change that profile to match wild sturgeon, yet it’s not from a wild sturgeon. We can drive these oocytes to have the same fatty acid composition of wild sturgeon.”

The lab-grown caviar project is a collaboration with scientists from University College London. Darren Nesbeth, UCL’s associate professor of synthetic biology, said it is ‘less technically challenging’ to match the taste of regular caviar with an analogue caviar or a lab-grown caviar than to match the mouthfeel and aroma of other meat such as salmon, chicken or beef. “It's a far less complex material, physically and biologically. Any challenges we do face in achieving that taste will be much lower than people making more complicated foods.”

Functional food possibilities

He therefore agreed lab-grown technology can potentially allow a larger consumer audience to enjoy caviar’s unique taste and nutritional benefits. “There's a whole new potential market we have here,” he said. “We've got more capability to value-add to traditional caviar. For example, there are certain health benefits and constituents and nutrients in natural caviar. We have control of those dials now and can turn those dials up now. And with our approach you know that these are still authentic sturgeon-derived proteins from various different species of sturgeon.”

Caviar is rich in Omega-3 fatty acids, B Vitamins, vitamin D and calcium and contains a variety of natural essential amino acids such as lysine, arginine, isoleucine, methionine and histidine. It therefore has promise as a functional food for the mass market. "We could easily increase the levels of AAT1 and melanin in our caviar to make it a functional food,” Benning said. “Functional foods in Japan, China, South Korea are old school. We're quite behind in Europe.”

Caviar also contains Superoxide dismutase, he said. "Basically, that's your Rolls-Royce of antioxidants. That's in abundance in caviar. If we can bring the price down, then people can be eating it all day long just like they do pomegranates and chia seeds.”

Futureproofing the caviar sector

Nesbeth added that Benning and his group of companies are ‘clearly steeped in the old school traditions of caviar culture, sturgeon farming and animal welfare’. “He's not a Silicon-Valley type,” he joked. “This is an evolution of a legacy player. He's future proofing the business. Ken's caviar concept can still be in play in 30 years’ time when we've got our carbon down. It will survive this transition.”