Why is the Netherlands’ adoption of Nutri-Score so controversial?

After ‘careful consideration’ and review by the Health Council of the Netherlands, Dutch secretary of state for health Maarten van Ooijen announced a voluntary nutrition labelling scheme will be introduced across the country: Nutri-Score.

The decision follows on on from the Dutch Ministry of Health’s National Prevention Agreement of 2019, which in part, aims to stem the growing rate of overweight in the country. The pact commits to introducing a single, widely recognised ‘healthy choice logo’ to make it easier for people to choose healthier foods in the supermarket.

With a couple of years’ delay, the nutrition labelling scheme has now been selected: from 1 January 2024, manufacturers and supermarkets in the Netherlands may officially use Nutri-Score on their packaged food and beverage products.

The Wheel of Five/Nutri-Score backstory

There has long been pushback against Nutri-Score amongst members of the Netherlands' nutritional science community, who argue the front-of-pack (FOP) labelling scheme contradicts the country’s food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG).

Just as the UK has its ‘Eatwell Plate’, the practical information tool used by the Netherlands Nutrition Centre to illustrate its FBDG is known as the ‘Wheel of Five’. It recommends a dietary pattern offering the ‘best’ combination of health benefits and nutrient provision, based on traditional Dutch foods. The Wheel of Five, in its first iteration, was developed in 1952.

Today, the Netherlands' Wheel of Five recommendations include lots of fruit and vegetables; whole grain products; less meat and more plant-based food; sufficient dairy products; a handful of unsalted nuts; soft or liquid spreadable fats; and enough fluid, such as water, tea and coffee.

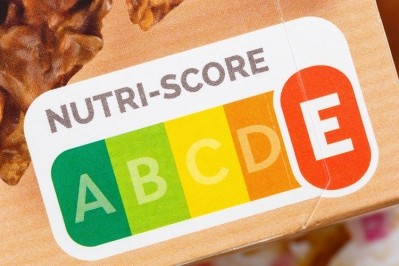

Nutrition labelling scheme Nutri-Score, on the other hand, was developed in France in 2017. Its algorithm ranks food from -15 for the ‘healthiest’ products to +40 for those that are ‘less healthy’. Based on this score, the product receives a letter with a corresponding code: from dark green (A) to dark red (F).

Contradictions between the Wheel of Five and Nutri-Score have been well publicised. Back in 2019, then secretary of state for health Paul Blokhuis noted Nutri-Score’s algorithm did not ‘always comply’ with Dutch dietary guidelines, according to research from the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and the Netherlands Nutrition Centre.

Indeed, the two bodies criticised Nutri-Score for being ‘too positive’ about white bread and ‘too negative’ about olive oil compared to Dutch dietary advice.

In response, the Scientific Committee of the Nutri-Score (ScC) – a transnational government made up of representatives from Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland – updated the front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition label’s algorithm.

But still, members of the Netherlands’ nutritional science community oppose Nutri-Score.

Updated algorithm ‘better suited to the Dutch situation’

Changes to the algorithm sought to better align the nutrition label with dietary recommendations, by improving the differentiation between whole grain food rich in fibre and refined foods, for example. It also sought to better classify oils with lower contents of saturated fat (e.g., olive, walnut, rapeseed).

According to the Dutch government, the updated algorithm is ‘better suited to the Dutch situation’. “For example, the new method greatly improves the distinction between wholemeal bread and white bread because wholemeal bread usually gets an A and white bread mainly gets a C. Frozen pizzas usually do not score higher than a C with the revised algorithm.”

Despite this improvement, the algorithm is still ‘not perfect’ in the eyes of the government, which suggested further developments and improvements be made.

“We should really see Nutri-Score as something extra that we can all use in the supermarket. Eating as much as possible within the Wheel of Five remains the healthiest advice for everyone. In addition, the Nutri-Score offers an extra handle to make the better choice, for example, for products that are not in the Wheel of Five,” said van Ooijen on Monday.

“In short: frozen pizza every day is not healthy. But if you eat it once, Nutri-Score can help you find the pizza with the best composition.”

Serge Hercberg, professor of nutrition at the Université of Sorbonne Paris Nord’s Faculty of Medicine, whose work formed the basis of Santé Publique France’s Nutri-Score, agrees ‘limited misclassifications’ were identified concerning some specific foods in FBDGs (not specifically in the Wheel of Five, but in all European FBDGs).

These were mainly in wholemeal cereal products vs refined products; some fatty fish; low-salt hard cheeses; skimmed and partially skimmed milks vs plain milk; and some sugared cereals and prepared meals.

“These points were improved in the framework of the update of Nutri-Score by the ScC,” Hercberg told FoodNavigator “The specific modifications of the calculation of the algorithm proposed by the ScC improve the situation and allow better consistency with dietary guidelines,” he said, including the Wheel of Five.

“Scientists (and especially Dutch scientists) who called for better coherence of the classification of food by Nutri-Score and the FBDG [should] be satisfied with the improvements made on most of the major points of discordance. It should be remembered that the discrepancies were limited and the improvements made must meet their expectations.”

‘Non-alignment with Wheel of Five will confuse consumers’

But not all agree Nutri-Score’s new algorithm is an appropriate tool to be used in the Netherlands, even as ‘something extra’ consumers can lean on in the supermarket.

According to the Dutch Dairy Association (NZO), which represents the interests of 13 dairy companies (which process 98% of the milk in the Netherlands), adjustments to the algorithm have shifted Nutri-Score ratings for around one-third of products on the Dutch Food Composition Database (NEVO).

One-fifth of non-Wheel of Five products still receive a Nutri-Score A or B, while 25% of the products in the Wheel of Five score unhealthy Nutri-Scores, according to NZO: “This will continue to cause confusion among consumers,” noted the trade association.

The updated Nutri-Score algorithm for solid foods has received more criticism still from members of the Netherlands’ nutritionist community, who are campaigning for Nutri-Score to align with the Wheel of Five and the government’s National Approach to Product Improvement (NAPV) ahead of adoption.

In correspondence penned to the government in February, nutrition scientists argued Nutri-Score presents an opportunity for the retailers and manufacturers able to ‘flaunt a Nutri-Score A’, which under the present algorithm, would be a ‘big loss’ for consumers and patients.

The group accuses Nutri-Score of ‘health-washing’, and argues the nutrient labelling scheme undermines the government’s NAPV. “Nutri-Score undermines the NAPV because it is based on a calculation of ‘favourable’ and ‘unfavourable’ nutrients. And certain products contain so many ‘favourable’ nutrients that there is plenty of room to still add extra salt or sugar. Or conversely, an unhealthy product can still get a good Nutri-Score by adding ‘favourable’ nutrients such as protein or vegetable powder’.

The campaign was led by Dutch consultancy Voedingsjungle, which specialises in children’s nutrition, and supported by more than 180 nutritionists and physicians.

Are other forces at play?

As to why Nutri-Score was adopted as the official, voluntary labelling scheme of choice in the Netherlands, NZO’s Stephan Peters believes there might be other forces at play.

Until now, Nutri-Score was not officially adopted in the Netherlands, and yet, the labelling scheme has been appearing on supermarket shelves since 2019, explained Peters, who heads up nutrition research and food law at the trade association.

He believes retailers and consumer organisations have been lobbying for its formal adoption, and secretary of state for health van Ooijen has yielded to the pressure.

Five big supermarkets dominate the food retail sector in the Netherlands, and Peters suspects van Ooijen’ decision to side with these players on Nutri-Score was strategic.

“The secretary of state for health needs the supermarkets [on his side] for other food policy issues. It’s a bit of giving and taking,” he told FoodNavigator, stressing this was his personal opinion only.

“But still, it’s strange that all your food and behavioural scientist advise you not to do it, but you still introduce it.”

When the ScC adjusted the Nutri-Score algorithm for solid food late last year, the Health Council of the Netherlands advised the government the labelling scheme could be a ‘useful addition’ to existing nutritional information.

At the same time, the Health Council noted the label has ‘shortcomings’, which ‘need to be addressed as a matter of priority’.

It is likely van Ooijen heeded the Health Council’s advice, suggesting Nutri-Score exist alongside existing nutritional information, rather than that offered by nutritional and scientists, we were told.

‘A complementary tool’

For the Université of Sorbonne’s Hercberg, it is right that Nutri-Score accompany FBDGs, because their objectives are different but complementary.

“FBDGs aim to drive consumers towards a healthy diet providing consumers practical guidance about what is considered a healthy diet, giving general information about consumption of broadly defined food groups to help consumers identify which food groups…should be encouraged or limited,” the professor told this publication.

Sometimes a quantitative frequency of consumption is provided, and qualitative advice offered for specific nutrients, such as limiting salt, sugar or fat intake. “While we may identify a diet as healthy or unhealthy, by its association with various health outcomes…the same cannot be said for individual specific foods.”

FOP labelling schemes such as Nutri-Score, on the other hand, do not refer to overall diet. Rather, it rates specific foods. This, explained Hercberg, is why Nutri-Score does not classify foods as ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ in absolute terms. “Such a purpose for a nutritional FOP label would be questionable since absolute healthiness depends on the amount of food consumed and the frequency of its consumption, but also on the overall dietary balance of individuals.”

Further, FBDGs recommend food groups, within which a large variability in composition exists, explained Hercberg. Under the definition of ‘fish’, for example, one may consume raw, canned, smoked, patty, breaded or minced fish. “The Nutri-Score provides additional information: fresh salmon ranks A, canned salmon ranks B, and smoked salmon D…

“Therefore, the Nutri-Score is truly complementary to the FBDGs (such as Wheel of Five) because it can help consumers adjust the quantity and frequency of consumption of [for example] different types of salmon product in an easy way.”